LATASHA PULLIAM | Death Row Clemency | 19yo Female Sexual Sadist Charged With 131 Counts of MUR, AGG SEX A-V CH, AGG KID, AGG UR, in Connection With the Sexual Assault and Death of a 6yo Girl | Autographed Letter Signed

LongfellowSerenade 67

Latasha Pulliam was convicted of the murder, sexual assault, and kidnapping of six-year-old Shenosha Richards in 1991. Pulliam and her boyfriend sexually assaulted, tortured and strangled her neighbor’s 6-year-old daughter in Chicago. Pulliam and Jordan sexually assaulted the girl with a shoe polish applicator and a hammer, and then used the hammer to pulverize her skull. Pulliam confessed to shutting the girl in a closet until she suffocated, and then hiding the body in a garbage can. She received the death penalty for the murder conviction. Her convictions and sentences were initially upheld but were later subject to appeals and post-conviction proceedings. These proceedings included an evidentiary hearing to determine if she was mentally retarded, potentially making her ineligible for the death penalty, as per the Atkins v. Virginia ruling. The post-conviction petition also raised claims of ineffective assistance of counsel. Latasha Pulliam was among the Illinois death row inmates whose sentences were commuted by Governor George Ryan on January 12, 2003

… a female John Wayne Gacy

$50.00

- Postage

-

Standard Shipping

$0.00 to United States

Get Additional Rates

- Select Country

- Zip/Post Code

- Quantity

Description

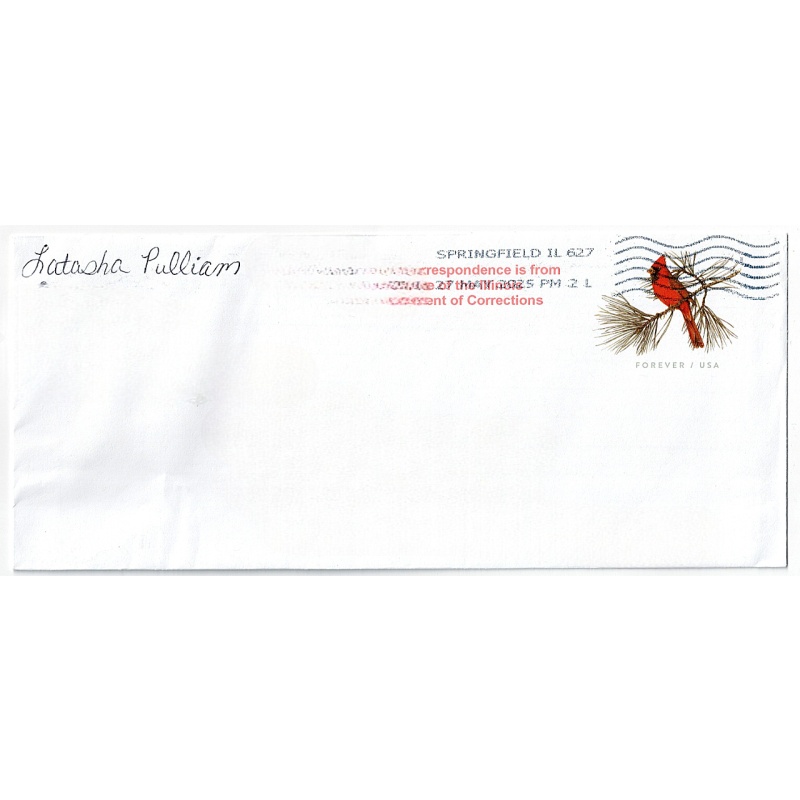

Latasha Pulliam. Autographed Letter, Signed. Handwritten, Commercial #10 (4.125 × 9.5 envelope). Springfield, IL. May 27, 2025. Content unknown. SEALED.

This is the unflinching chronicle of Latasha Pulliam, a young Chicago woman whose history of abuse, intellectual disability, and substance use converged in a violent crime of unspeakable brutality. It traces her troubled upbringing, the abduction, torture, and murder of six‑year‑old Shenosha Richards on March 21, 1991, the legal battles that followed—including her death sentence and its commutation—and the broader repercussions of her case. It seeks clarity on how cumulative trauma and systemic failures can create a path to atrocity, and what society must do to prevent such tragedies. An autographed item from Pulliam, given the rarity of her notoriety, would be a unique and coveted piece in any true crime collection.

Echoes of Violence

On April 11, 1971, Latasha Love Pulliam was born in Cook County, Illinois. Raised in a household marked by alcoholism, neglect, and sexual abuse, she would later be diagnosed with mild intellectual disability, her IQ testing around 69. That barely concealed a mind battered by trauma from infancy. Hospital records revealed near‑drowning at 22 months and febrile seizures, injuries dating back to a childhood marked by violence. Her education never advanced beyond early grade school; either expelled or withdrawn repeatedly, she never found stability in any institution.

Her employment history mirrored her fragmented life—sporadic jobs at fast‑food outlets, occasional domestic work, and intermittent day labor. By age fourteen, she was pregnant, and a few years later, she was already the mother of two children. Both were born drug-addicted, each with a different father. One of the babies, at age 1½, was beaten, raped, and then put up for adoption. Substance abuse, chiefly cocaine, became a near-constant presence as she drifted between low‑income apartments in Chicago’s South Side.

Latasha’s circle included her live‑in boyfriend, Dwight Jordan, a few acquaintances from jail, and a rotating cast of neighbors. One friend later recalled Latasha speaking proudly about violence, her demeanor cold and unnerving.

On a spring day stained by unthinkable cruelty, she crossed a moral Rubicon. On March 21, 1991, six‑year‑old Shenosha Richards, a neighbor’s daughter, was lured into Latasha’s third‑floor apartment by promises of treats or a TV show. Once inside, Latasha ushered Shenosha into the bedroom with Jordan and retreated to use cocaine. What unfolded next was a savage orchestration of sexual and physical torture: Jordan attempting to penetrate the child with a shoe‑polish bottle, and Pulliam inserting a hammer into her vagina, alternating with bondage and strangulation. After about ten excruciating minutes of assault, Latasha choked Shenosha with an electrical cord until she lost consciousness. She then moved the dying child to a nearby vacant apartment, choking her for ten more minutes when the child mentioned her parents. When Latasha found Shenosha dead in a closet, she struck her skull repeatedly with a hammer, stuffed her body into a garbage can, and used trash to conceal the corpse. Autopsy revealed forty‑two distinct injuries—lacerations, punctures, skull fractures, internal bleeding—evidence of a willful and sadistic act.

Shortly after, Chicago police arrested Pulliam at the scene. At the Cook County courthouse, she provided a taped, detailed confession recounting the murder and the methodical disposal of the body. Both Pulliam and Jordan were charged with first‑degree murder, two counts of aggravated criminal sexual assault, and two counts of aggravated kidnapping.

The Cook County trial, held in 1996, laid bare every element of the crime. Prosecution witnesses included medical examiners who detailed each injury sustained by Shenosha and fellow inmates who testified that Pulliam bragged of the murder and sexually assaulted another inmate while jailed. Pulliam’s defense leaned heavily on her intellectual impairment, her history of childhood and drug‑related trauma, and expert opinions suggesting susceptibility to influence and poor impulse control. But the jury found no basis for leniency. By late summer 1997, Latasha Pulliam was convicted and sentenced to death. She received additional consecutive terms—60 years for one sexual assault count, 30 for the second, and 15 for kidnapping.

Appeals to the Illinois Supreme Court upheld the rulings. In 2002, following the U.S. Supreme Court’s Atkins decision prohibiting execution of the intellectually disabled, the State Supreme Court ordered a hearing on her mental capacity. That hearing led to her sentence being commuted. In January 2003, Illinois Governor George Ryan commuted her death sentence, along with every other woman on death row at that time. Pulliam remains incarcerated at Logan Correctional Center, serving life plus 105 years with no parole. She is classified both a violent and sexual offender, with no record of genuine remorse or engagement in rehabilitation programs; institutional records describe repeated infractions and an absence of psychological growth.

This case left one direct victim—Shenosha Richards, whose brief life ended in brutal pain. The psychological damage extended to an entire community: parents, neighbors, courtroom attendees, where the crime shattered any sense of innocence and trust. Media reaction was one of horror and outrage; her case became a touchstone in debates over mental competency, capital punishment, and the responsibilities parents and communities bear in safeguarding children. In the wake of the crime, activists campaigned for better child protection and monitoring of at-risk families, though no specific laws passed; still, it spurred increased funding for early-intervention programs.

Pulliam’s case forces society to confront the stark question: when does a victim of trauma become a perpetrator? Her intelligence deficits, childhood abuse, and drug addiction created a biography as tragic as it was depraved. But such backgrounds—however harrowing—do not justify crime. Few lessons are more pressing: children in high‑risk families must be identified and supported, mental disabilities must be evaluated within criminal liability, and caretakers must be held accountable before crises become catastrophes.

From a collector’s perspective, an autograph from Latasha Pulliam would be exceedingly rare—a prison signature from one of the few women to have received the death penalty (albeit never carried out) in Illinois, tied to perhaps the most gruesome child‑murder case in Chicago’s modern history. That scarcity and infamy would give it a peculiar value among criminological mementos and true‑crime relics.

In closing, the story of Latasha Pulliam stands as a harrowing testament to cycles of violence, lost childhoods, and institutional failure. It is a case that forces reflection on how trauma, neglect, disability, and drugs can coalesce into tragedy—and how only through vigilance, early support, and communal responsibility can we hope to prevent another Shenosha from ever being born into such devastation.

- VIDEO: Death Row Stories: Latasha Pulliam | https://youtu.be/W9jIe2yuCTE

- VIDEO: Women On Death Row Latasha Pulliam most excited crime story | https://youtu.be/J4W1hveW2oQ

Archiving Protocol:

• Handled with White Gloves ab initio

• Photo Pages/Sheet Protectors: Heavyweight Clear Sheet Protectors, Acid Free & Archival Safe, 8.5 × 11, Top Load

• White Backing Board—Acid Free

Shipping/Packaging: Rigid Mailer 9.5 × 12.5. The Kraft cardboard is white, self-seal, and stay-flat, ensuring it does not bend. Heavy cardboard, which has strong resistance to bending and tearing, makes each rigid mailer sturdy. These mailers are significantly thicker than those used by the USPS. Shipping cost is never more than it absolutely has to be to get it from me to you.

Payments & Returns

- Payment Methods

- PayPal, Money Order

Postage & Shipping

- Item Location

- 49858, Michigan, United States

- Ships To

- Worldwide

- Pick-ups

- No pick-ups

- Shipping Instructions

- Shipping costs to international destinations will be applied to this auction. Please contact us if you have any questions about shipping to your location.

- Returns Accepted

- No

-800x800.jpg)

-800x800.jpg)

-800x800.jpg)

-500x500.jpg)