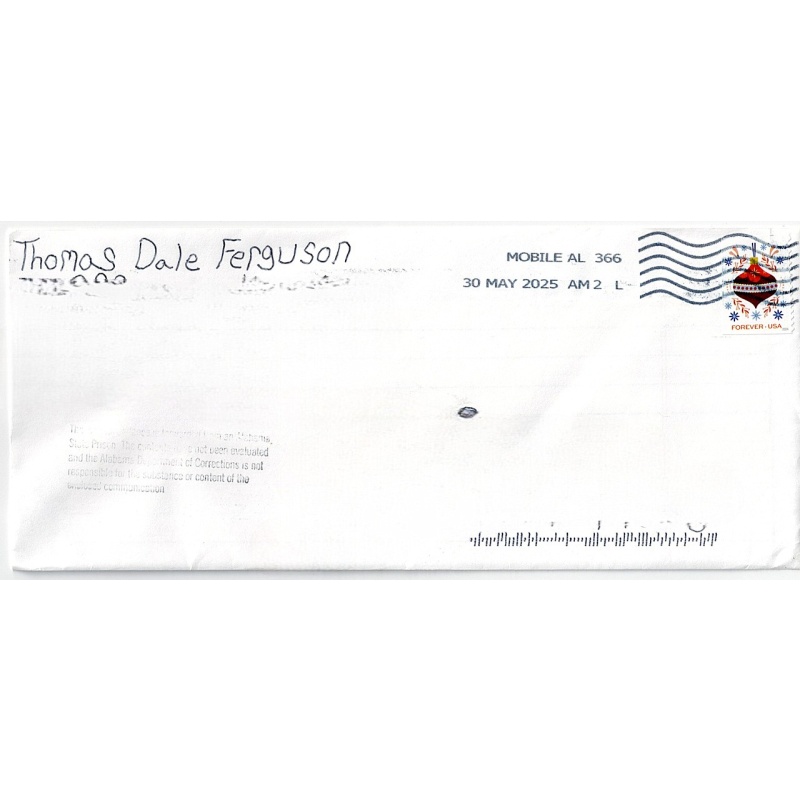

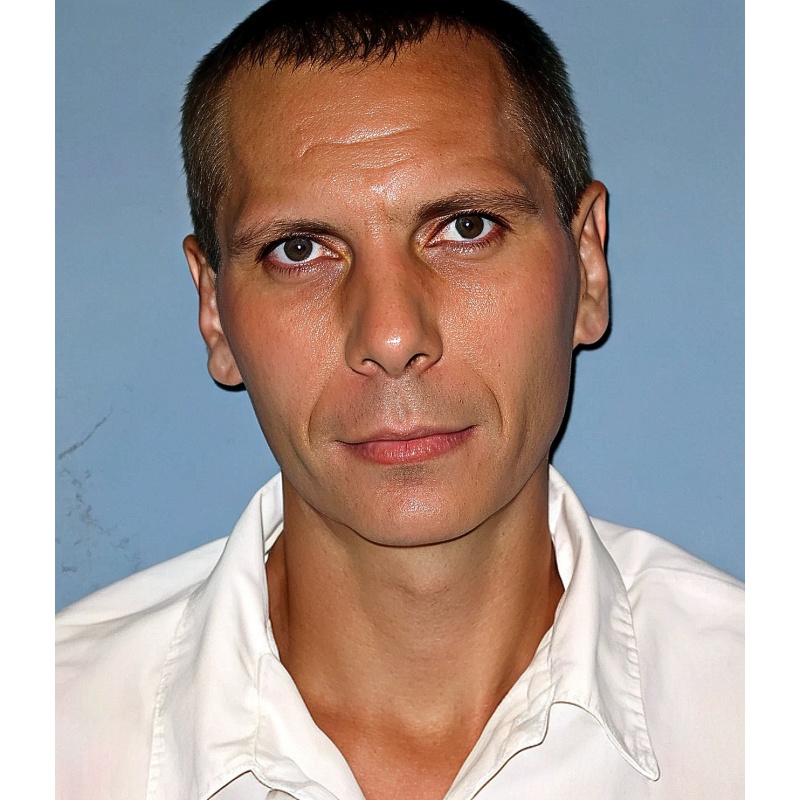

THOMAS DALE FERGUSON | On Death Row for 27 Yrs | Robbery-Motivated Double Homicide of Harold and Joey Pugh | Autographed Letter Signed

LongfellowSerenade 67

Harold and Joey Pugh were murdered on July 20, 1997, during a fishing trip in Alabama by a group of men intending to steal their truck. Thomas Dale Ferguson and Michael Craig Maxwell were convicted of capital murder and sentenced to death; Ferguson's sentence involved judicial override. The other perpetrators, Donald Ray Risley, Keno Fleando Graham, and Mark David Moore, received varying sentences, including life in prison. Ferguson has exhausted numerous appeals, including to the U.S. Supreme Court, and remains on death row at Holman Correctional Facility as of June 18, 2025. The case has raised legal issues regarding judicial override and the role of the jury in capital sentencing.

$30.00

- Postage

-

Standard Shipping

$0.00 to United States

Get Additional Rates

- Select Country

- Zip/Post Code

- Quantity

Description

Thomas Dale Ferguson. Autographed Letter, Signed. Handwritten, Commercial #10 (4.125 × 9.5 envelope). Mobile, AL. May 30, 2025. Content unknown. SEALED.

A Quiet Stream, A Brutal Dark

In the predawn mist of July 20, 1997, a father and son embarked on an ordinary morning of fishing by the gentle currents of Cane Creek Canyon. What unfolded that day would shatter the community’s trust and leave a haunting legacy: a planned getaway would transform into a cold-blooded double murder, and in its aftermath, one man—Thomas Dale Ferguson—would watch his life unravel into a death sentence.

Thomas Dale Ferguson was born on July 20, 1973, in Sheffield, Alabama. He grew up in a working-class household; although details of his parents remain scarce, those who knew him remember a quiet, inward child whose early life offered little foreshadowing of violence. Ferguson attended local schools but showed no signs of academic distinction. In his early twenties, he drifted through low-wage jobs—construction, landscaping, odd jobs—never finding stability, never anchoring himself in steady work or relationships.

By mid‐1997, Ferguson had aligned himself with a group of men—including Michael Craig Maxwell, Mark David Moore, Keno Fleando Graham, and Donald Ray “Donnie” Risley—with vague promises of a bank robbery in nearby Belmont, Mississippi. Little about their preparation—cheap firearms, rented motel rooms, and hurried plans—suggested sophistication. But one thing became clear: they needed a vehicle. Thus, the Pugh family’s modest truck became their target, and where opportunity and desperation met, horror followed.

On the morning of July 20, Harold Alan Pugh, aged 41, and his son Joey, age 11, drew their fishing boat to Cane Creek’s banks. The day was humid and still. Horton Maxwell and Ferguson, armed and unrelenting, confronted the pair. Maxwell forced them back into the boat; Ferguson joined, pistol in hand. What ensued was raw and horrific: Maxwell shot Joey twice, the small body silent in the current. Ferguson squeezed the trigger on Harold. By the time the second shot rang, the father and son lay lifeless in the boat, their morning ritual shattered by violence. The perpetrators dumped the bodies into the creek, stole the truck, and carried out their planned bank robbery the following day—discarding the vehicle afterward, soaked in gasoline, a burned testament to their brutality.

When the Pughs were reported missing, the Catalytic response began. Their bodies surfaced in the creek later that day, discovered by a friend. The autopsy confirmed gunshot wounds: two to each head. Evidence mounted—spent 9 mm cartridges, the abandoned boat seat, and later, the diaries of accomplices who broke under pressure. Five were arrested in late August 1997, and grand juries quickly returned compelling indictments.

Ferguson was indicted in September 1997 on four counts of capital murder. His trial began on June 22, 1998, in Colbert County Circuit Court. The jury swiftly convicted him on all counts. By jurors’ vote, 11–1, they recommended life imprisonment without parole. Yet the presiding judge, invoking Alabama’s judicial-override statute, overruled them—calling the murders “heinous” and Ferguson’s withdrawal opportunity unheeded—and imposed death instead.

On appeal, Ferguson argued numerous procedural missteps, including the use of nonstatutory aggravating factors and insufficient consideration of his mental health. The Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals and Supreme Court affirmed his conviction and sentence—finding no reversible error. Federal appeals met the same fate: repeated denials in District and Appeals Courts and a final U.S. Supreme Court rejection in February 2024. As of 2025, he and Maxwell remain on death row at Holman Correctional Facility.

Two lives were stolen—the identity of the Pughs cemented in memory, two hearts torn from a family and community. Public outcry, chilling and righteous, followed. Media screamed of the grotesque nature of murdering a child, and policymakers in Alabama debated—and by 2017 eventually abolished—the law allowing judges to override jury life recommendations.

Ferguson sits in death row’s isolation, a stark presence in legal tragedy. He has pursued appeals, claimed mental deficiencies, yet received no clemency or retrial. Rehabilitation efforts are nonexistent; his case poses no realistic chance of remission. As for future risks—he poses none to society except for the enduring psychological scars left on the Pugh family, the trauma still reverberating through the region.

What lessons can we draw? The tangential danger of judicial override, the imperative for thorough vetting of criminal intent and mental health, and the sobering impact of violence on ordinary people. Promoting jury authority, supporting victims’ healing, and stringent mental-health assessment before sentencing seem the only sure defenses against repeat tragedies.

And, somewhat paradoxically, should you value rarity—and the morbid intrigue of criminal memorabilia—an autographed item from Ferguson would indeed be rare. Given his incarceration and obscure profile, any authenticated piece—whether a signed letter or sketch—would be exceedingly scarce and likely to intrigue certain collectors. Yet its value remains subjective, weighed against ethical concerns.

This narrative remains rooted in the facts, drawing from court records, autopsy reports, media archives, and appellate opinions. It refrains from conjecture, preserving an objective lens while telling the story of two lives cut short, five men whose fates diverged in prison, and a system that made history—the hard way.

Summary

Reflection

Ferguson’s

case demonstrates how ordinary desperation, mixed with poor choices

and judicial discretion, can manifest in extraordinary crimes. It

also underscores systemic flaws—chief among them legal overrides

and under-assessed mental evaluations. The tragedy of Harold and Joey

Pugh serves as a cautionary tale, and the legal reforms it spurred

stand as a testament to the community’s resilience. However macabre

the fascination, the hardest lesson remains simple: vigilance in

justice matters, and life must never be taken lightly.

VIDEO: Family at Hearing in Ferguson Case | https://youtu.be/-Nyk_PLSHss

Archiving Protocol:

• Handled with White Gloves ab initio

• Photo Pages/Sheet Protectors: Heavyweight Clear Sheet Protectors, Acid Free & Archival Safe, 8.5 × 11, Top Load

• White Backing Board—Acid Free

Shipping/Packaging: Rigid Mailer 9.5 × 12.5. The Kraft cardboard is white, self-seal, and stay-flat, ensuring it does not bend. Heavy cardboard, which has strong resistance to bending and tearing, makes each rigid mailer sturdy. These mailers are significantly thicker than those used by the USPS. Shipping cost is never more than it absolutely has to be to get it from me to you.

Payments & Returns

- Payment Methods

- PayPal, Money Order

Postage & Shipping

- Item Location

- 49858, Michigan, United States

- Ships To

- Worldwide

- Pick-ups

- No pick-ups

- Shipping Instructions

- Shipping costs to international destinations will be applied to this auction. Please contact us if you have any questions about shipping to your location.

- Returns Accepted

- No

-800x800.jpg)

-500x500.jpg)