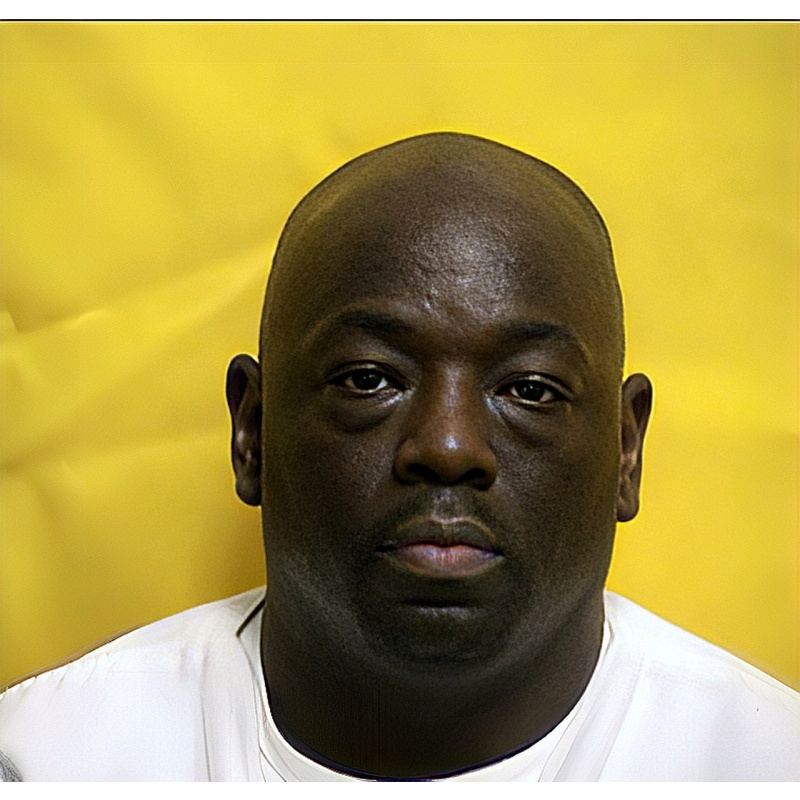

GREGORY B. MCKNIGHT | Death Row | Serial Killer Murdered Three People in Ohio, Burying the Bodies of Two on His Property in Chillicothe Afterwards | Autographed Letter Signed

LongfellowSerenade 67

Gregory McKnight, an American serial murderer, was born in 1976 and sentenced to two murders in 2000. He was convicted in juvenile court and served a brief time before being freed in 1997. In 2000, he kidnapped and murdered Gregory Julious, dismembering his body and burying it on his Vinton County, Ohio home. Six months later, he and two acquaintances broke into a home and stole firearms. On November 3, 2000, he kidnapped Emily Murray, a 20-year-old Kenyon College student and coworker, fatally shooting her and hiding her body in his trailer. McKnight was tried in 2002 and found guilty of aggravated murder, murder, abduction, aggravated robbery, receiving stolen property, and complicity. He is currently awaiting death at Chillicothe Correctional Institution. McKnight's attorney contended that racial bias impacted the state's choice not to charge him with kidnapping Julious, who was Black, but with kidnapping Murray, who was white.

You see

the good thing about knowing and accepting

that you're going to be murdered

is you can tell the truth that's never been told

without regrets

Death is freedom.

$40.00

- Postage

-

Standard Shipping

$0.00 to United States

Get Additional Rates

- Select Country

- Zip/Post Code

- Quantity

Description

Gregory McKnight. Autographed Letter, Signed. Handwritten, Commercial #10 (4.125 × 9.5 envelope). Columbus, OH. May 28, 2025. Content unknown. SEALED.

This is the harrowing story of Gregory B. McKnight: a teenage killer turned cold-blooded murderer whose murderous trajectory spanned a decade. Born in Queens in 1976, McKnight committed his first homicide in Columbus, Ohio, at age 15. Released from juvenile detention in 1997, he appeared to rebuild his life—marrying a Youth Center employee—until between May and November 2000 he abducted, dismembered, and murdered two young men, hiding their remains on his property in rural Vinton County. Influenced by financial desperation? Jealousy? These motives remain murky. His arrest came after police discovered his third victim’s car in his driveway. Sentenced to death in 2002, his convictions were upheld by Ohio’s Supreme Court in 2005. With appeals exhausted, he remains on death row, a rare candidate for execution. His case sparked questions about juvenile rehabilitation, death-penalty geography, rural court funding, and the risks of secretive pioneer life. A piece of his autographed memorabilia would be tragically rare, a disturbing artifact of a mind turned murderous.

The Silence Behind the Smile

Gregory

B. McKnight was born on November 14, 1976, in Queens,

New York. He spent his formative years in a working-class urban

neighborhood, one of several children in a household affected by

instability and scant oversight. Sometime in early adolescence, his

family relocated to Columbus, Ohio. There, he struggled academically,

drifting through local schools with mediocre grades, no

extracurricular involvement, and frequent disciplinary disciplinary

referrals.

By age 15, he had begun running with a troubled

peer group. In 1992, at just fifteen years old, McKnight carried out

his first murder: he robbed and fatally shot a man in Columbus—a

crime that earned him a juvenile conviction and a stint at the

Circleville Youth Center. Prosecutors labeled him a danger even at

that age. Yet after serving only five years, he was released in

1997.

Upon his release, McKnight married a woman named

Kathryn, an employee of the very Youth Center where he had been

incarcerated. For a spell, he appeared to attempt normalcy—finding

work at a local restaurant and living quietly in rural Vinton County,

Ohio. He formed connections with co-workers, including a

twenty-year-old named Emily Murray, and maintained casual

friendships—among them, Gregory Julious, who visited McKnight

through shared acquaintances.

But over the early spring of

2000, the old impulses resurfaced. On May 13, McKnight lured his

acquaintance Gregory Julious, twenty years old, to his trailer under

the guise of friendly conversation around 4 p.m. Once inside, he

suddenly shot Julious, then dismembered the body and concealed it on

his property—burying or hiding parts in the yard and cistern. That

body remained undiscovered for months.

McKnight lay low

until October 11, when he and two unnamed acquaintances burglarized a

residence, stealing firearms. The crime drew scant attention at the

time, but it would become part of the broader pattern of escalating

violence and secrecy.

Then on November 3, at nightfall,

McKnight stalked another twenty-year-old—Emily Murray—his

restaurant co-worker. He followed her home from her shift, kidnapped

her, and transported her to his trailer. There, he shot her once in

the head, wrapped her body in a carpet, and stashed it inside. Again,

he concealed the evidence, confident in his rural solitude.

It

was not until December 2000 that law enforcement finally closed in.

Murray’s car, found parked in McKnight’s driveway, set off

alarms. When police searched the property, they discovered her

decomposed remains in the trailer and unearthed bones matching those

of Julious. His wife Kathryn was initially taken into custody but

later cleared once investigators ruled out any involvement.

McKnight

was arrested and charged: aggravated murder, kidnapping, aggravated

robbery, murder, evidence tampering, and abuse of a corpse. At trial

in October 2002, the rural Vinton County jury convicted him of

murdering both Julious and Murray, along with related felony counts.

They unanimously recommended the death penalty—imposing it for the

killing of Emily Murray while committing kidnapping and robbery.

In

2005, the Supreme Court of Ohio upheld both his convictions and his

sentence, affirming that the state had proven beyond a reasonable

doubt that he committed two separate murders and had concealed his

victims to avoid detection. His death sentence remains in place,

making him one of only a handful of Ohio death-row inmates.

The

number of victims officially stands at two, though the brutality of

the crimes—the dismemberment, concealment, and cold stalking—left

a deep psychological toll in the Ohio community. Murray, a promising

college student, left a family shattered by grief; Julious’s

disappearance had haunted Columbus for months. The publicity of the

case reignited debate about juvenile crime rehabilitation, the

fairness of death-penalty trials in underfunded rural counties, and

the difficulty of promptly locating missing persons in sparsely

populated areas.

McKnight remains incarcerated in Ohio’s

death-row facility. He has petitioned for appeals, citing issues like

racial bias in jury selection and inadequate defense representation,

but to date his legal challenges have failed. No credible

rehabilitation efforts have been documented; he refuses interviews

and remains isolated, with little engagement beyond legal

counsel.

As for future threats, McKnight remains locked

away. But the pattern—early violent acts, a decade of apparent

calm, then explosive brutality—casts a shadow over any attempts at

redemption.

Lessons from this case are manifold. It shows

the challenges of juvenile justice—how early crimes left

inadequately addressed can evolve into serial violence. It highlights

how rural justice systems struggle to secure equitable trials,

especially when funding is limited. And it reminds us how dangerous

individuals can hide in plain sight—neighbors in a trailer park who

blend into community life until horror emerges.

Strangely,

true‑crime collectors have begun whispering about the value of

McKnight memorabilia. An autographed letter or drawing from him would

be exceptionally rare, a chilling collectible for those fascinated by

notorious killers. While disturbing, its rarity ensures high market

value among true‑crime aficionados.

Through Gregory

B. McKnight’s story, we see the fragile boundary between

rehabilitation and recidivism, the stark consequences of failing to

reconcile early crimes, and the chilling depths to which a person can

carry violence into mid‑life.

VIDEO: Gregory McKnight: The Ohio Serial Killer’s Dark Secrets & Death Row Fate | True Crime Documentary | https://youtu.be/zFMt0j6u30c

Archiving Protocol:

• Handled with White Gloves ab initio

• Photo Pages/Sheet Protectors: Heavyweight Clear Sheet Protectors, Acid Free & Archival Safe, 8.5 × 11, Top Load

• White Backing Board—Acid Free

Shipping/Packaging: Rigid Mailer 9.5 × 12.5. The Kraft cardboard is white, self-seal, and stay-flat, ensuring it does not bend. Heavy cardboard, which has strong resistance to bending and tearing, makes each rigid mailer sturdy. These mailers are significantly thicker than those used by the USPS. Shipping cost is never more than it absolutely has to be to get it from me to you.

Payments & Returns

- Payment Methods

- PayPal, Money Order

Postage & Shipping

- Item Location

- 49858, Michigan, United States

- Ships To

- Worldwide

- Pick-ups

- No pick-ups

- Shipping Instructions

- Shipping costs to international destinations will be applied to this auction. Please contact us if you have any questions about shipping to your location.

- Returns Accepted

- No

-800x800.jpg)

-800x800.jpg)

-500x500.jpg)

-500x500.jpg)

-500x500.jpg)

-500x500.jpg)