CHERIE LOUISE LASH-RHOADES | Death Row | Only Native American Woman in History Sentenced to Death for Mass Murder: Tribal Chair Receives Death Penalty for Shooting and Stabbing Spree That Killed 4 and Wounded 2 | ALS

LongfellowSerenade 67

Cherie Louise Lash-Rhoades (born December 13, 1969) was a former tribal chairwoman of the Cedarville Rancheria of Northern Paiute in Modoc County, California, who perpetrated a horrific mass shooting at a tribal council meeting on February 20, 2014. Once a community leader, Rhoades’s life unraveled amid allegations of embezzlement and a looming eviction from tribal housing. In a furious retaliation at a council hearing to banish her, she opened fire and killed four people – including three of her own family members – and wounded two others. Her crimes shocked the small, close-knit community and garnered national attention as an extremely rare case of a female mass murderer. Rhoades was swiftly arrested at the scene and later convicted of multiple counts of first-degree murder and attempted murder. She was sentenced to death in 2017 for what prosecutors deemed an intentional and premeditated massacre. This narrative nonfiction account traces Rhoades’s troubled path from her early life and rise to tribal leadership, through the deadly rampage and its aftermath, to her current imprisonment on California’s death row. It examines the motives, methods, and fallout of her actions – the devastated families of victims, the trauma to survivors, the media and public outcry – and considers the lessons learned from this tragedy, including the importance of addressing grievances and warning signs before they erupt into violence. Collectors of “murderabilia” have even noted that an autograph from Rhoades might be a macabre rarity, given the infamy and uncommon nature of her case

as victim impact statements were read describing the pain she caused,

she shook her head and rolled her eyes

$130.00

- Postage

-

Standard Shipping

$0.00 to United States

Get Additional Rates

- Select Country

- Zip/Post Code

- Quantity

Description

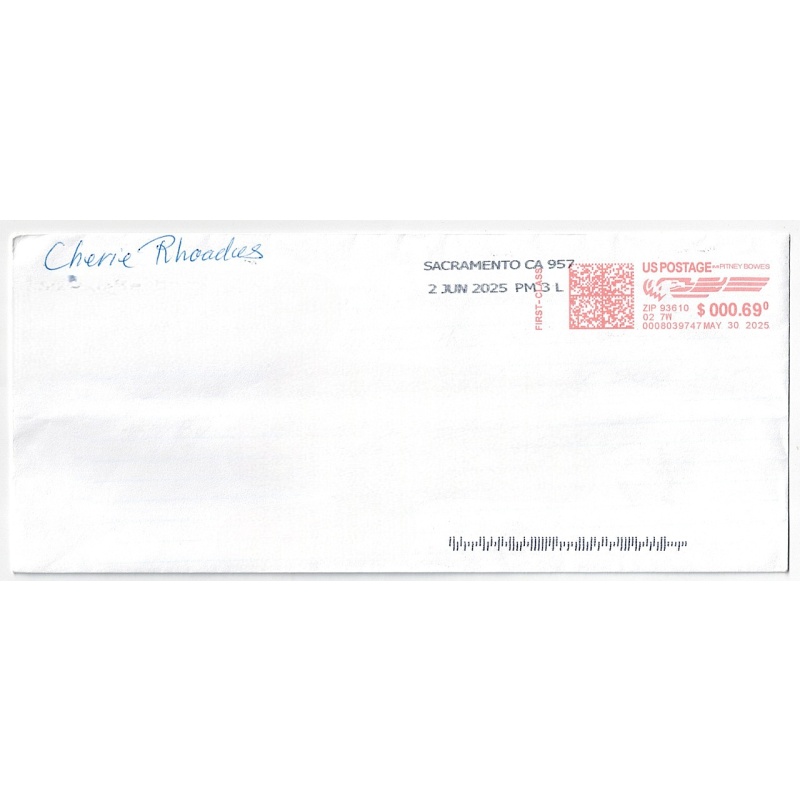

Cherie Rhoades. Autographed Letter, Signed. Handwritten, Commercial #10 (4.125 × 9.5 envelope). Sacramento, CA. June 2, 2025. Content unknown. SEALED.

Banishment to Bloodshed: The Cherie Lash-Rhoades Story

Early Life and Family Background

Cherie Louise Lash was born on December 13, 1969, into an impoverished Native American family in the remote Surprise Valley of northeastern California. She was a member of the Cedarville Rancheria, a federally recognized Paiute tribe with only a few dozen members. Raised in Modoc County, one of California’s most isolated regions, Rhoades grew up amid economic hardship and a tight-knit tribal community where nearly everyone was related. Her father, Larry Lash, and other relatives lived on the 26-acre Cedarville Rancheria, which consists of a small cluster of homes built in the 1950s. From a young age, Cherie was known by locals for her brash and aggressive demeanor. Neighbors and kin later recalled that merely hearing her name “could evoke a wince,” as she had a reputation for being confrontational and “a loudmouth” who often threatened to beat people up. One acquaintance described her as “a tangle of sheer meanness,” indicating that even before the crimes she would commit, Rhoades had long instilled fear and discomfort in those around her.

Despite these personal challenges, Rhoades’s early life remained rooted in family and tribal ties. She had multiple siblings, including a brother, Rurik Davis, and at least one sister, and she later became a mother herself. She married a man named Marvin Rhoades in 1999, taking his last name to become Cherie Lash-Rhoades. Together they raised a family on the rancheria; Cherie had a son, Jack Stockton, from a prior relationship, and also became a stepmother and grandmother figure through her marriage (Marvin’s daughter’s child referred to Cherie as “grandma”). The extended family network was complex and interwoven – for instance, one of Cherie’s nieces, 19-year-old Angel Penn, was actually raised in Cherie’s household from childhood after a relative could not care for her. These close familial bonds make the events that followed all the more tragic: many of Rhoades’s eventual victims and survivors were her own kin. Her early years offered few clues that she would one day betray those closest to her in an act of violent treachery, yet there were hints in her behavior – a hot temper, bullying tactics, and an inability to back down – that foreshadowed future conflict.

Rise to Leadership and Tribal Roles

In adulthood, Cherie Lash-Rhoades gradually assumed roles of responsibility in the small Cedarville Rancheria community. With only 35 enrolled members in the tribe (and about 18 adult voting members), leadership often fell to a handful of relatives. Rhoades became involved in tribal governance and local committees, likely leveraging her forceful personality. She served on a Native American healthcare clinic committee years earlier, where her volatility was already on display – a fellow committee member recounted an incident when Rhoades flew into a rage and hurled a table aside over a minor disagreement. Despite such episodes, Rhoades rose to prominence. By around 2010–2012, she had been elected (or appointed) as the Chairwoman of the Cedarville Rancheria, effectively the tribe’s top official. In this capacity she was responsible for administering tribal affairs, which included managing federal grants and overseeing the tribe’s modest enterprises. One tribal business was a gas station and convenience store in Cedarville, where Rhoades worked as an attendant and manager – locals recall her wearing bright tank tops that showed off her tattoos as she staffed the register.

As Chairwoman, Rhoades initially held significant sway over the community’s finances and operations. The Cedarville Rancheria did not have a casino of its own, but it received distributions of revenue from larger gaming tribes, and it earned income from the tribally owned gas station and nearby public scales. These funds were crucial for the welfare of the tiny tribe. Under Rhoades’s watch, however, rumors began to circulate about irregularities in the use of tribal money. By late 2013, federal authorities – including the FBI and Bureau of Indian Affairs – had opened an investigation into allegations that Rhoades had embezzled significant grant funds intended for the tribe. A sum of at least $50,000 was suspected missing, a huge amount for a community of that size. At the same time, discontent was growing among tribe members over Rhoades’s leadership style. She was perceived as autocratic and had accumulated enemies even within her family. In fact, many of the Cedarville members were blood relatives, and disputes quickly became personal feuds. The tribe’s general counsel, Jack Duran, later noted that “all of these folks are related,” describing the internal divisions as a tightly wound family conflict.

By early 2014, matters came to a head. Under the cloud of the federal theft investigation, the Cedarville Tribal Council suspended Cherie Rhoades from her chairwoman position in late January 2014. Her brother, Rurik Davis, 50, was appointed interim chairman in her stead. The council also initiated proceedings to evict Rhoades and her son, Jack Stockton, from their tribal housing, a severe step essentially akin to banishment from the reservation. The eviction was reportedly due to “unspecified reasons” tied to the misconduct allegations and perhaps general misbehavior. Rhoades bitterly resisted these moves. She lodged an appeal against the eviction, which led the Tribal Council to schedule a hearing on February 20, 2014, at the tribe’s headquarters in Alturas, the county seat, to formally consider her case. In the weeks leading up to that meeting, Rhoades’s anger simmered visibly. She made alarming threats about attacking people who “accused her of embezzling tribal funds,” threats that her own husband Marvin and other family members heard. Marvin later admitted that Cherie repeatedly ranted about “blowing them away” – language so extreme that he didn’t take it seriously at the time. Others in the community, too, knew Cherie as a bully with a fierce temper, but none imagined she would resort to actual violence. Tragically, they were wrong.

The Tribal Meeting Massacre (February 20, 2014)

On February 20, 2014, the tribal leadership convened an afternoon council meeting at the Cedarville Rancheria’s Alturas office to adjudicate Cherie Rhoades’s eviction appeal. It was an unseasonably warm winter day in Alturas, a rural town of about 2,800 people, but tension hung in the air among the roughly 18 adult tribe members gathered, along with a few children present in an on-site daycare room. Presiding over the hearing was Rhoades’s brother, Interim Chairman Rurik Davis. Also in attendance were several other tribal council members – many of them Rhoades’s own relatives – and the tribal administrator, Sheila Lynn Russo, who had been handling the paperwork related to Rhoades’s case. Cherie Rhoades arrived at the meeting with grim intent. Unbeknownst to the others, she had armed herself with at least two 9mm semi-automatic handguns, which she carried into the small council building hidden from view. The proceeding began normally as the council reviewed her eviction matter. But when it became clear that the tribe was prepared to expel her and her son for good, Rhoades snapped.

At approximately 3:30 PM, in the midst of the hearing, Rhoades suddenly pulled out a handgun and opened fire on the people in the room. The scene erupted into chaos and terror. Witnesses later recounted that Cherie first shot point-blank at those closest to her – which included her brother Rurik at the council table – and then kept firing methodically at others. According to police reports and court testimony, Rhoades fired every round she had, hitting a total of six people. Three of her family members were fatally struck by the gunfire: Rhoades shot her brother Rurik Davis, 50, who was the tribe’s chairman, as well as her 19-year-old niece Angel Penn and her 30-year-old nephew Glenn Calonicco. She also gunned down Sheila Russo, 47, the tribal administrator who was not related by blood but had worked closely with the family. These four victims had little chance to react or escape. One of the youngest victims, Angel Penn, was sitting with her newborn baby on her lap when Rhoades shot her; mercifully, the infant was not hit and was later recovered unharmed from his dying mother’s arms. Two other women were wounded by the gunfire: Melissa Davis and Monica Davis, both daughters of Rurik Davis (and thus Cherie’s nieces as well). They suffered gunshot injuries and collapsed as pandemonium engulfed the room.

Amid the screaming and smoke, some individuals made desperate attempts to flee. One tribal office employee managed to escape out a door, splattered with others’ blood, and sprinted approximately two blocks to the Alturas City Hall to get help. She burst into City Hall, “ringing the bell and screaming for help,” alerting officials that a massacre was underway at the tribal office. Back at the scene, Rhoades’s handgun ran out of ammunition after firing multiple shots into her relatives. However, her rampage was far from over. Enraged and undeterred, Cherie dashed into the small kitchen area of the building and grabbed a large butcher knife from a drawer. She then turned on one of the wounded survivors – later identified as one of Rurik’s daughters – and began stabbing the injured woman repeatedly, even as others in the room tried to intervene. Terrified witnesses later described it as a scene of unimaginable horror: four people lay dead or dying, two others bleeding from bullet wounds, and Rhoades lunging with a knife at anyone within reach.

At that moment, two things happened in quick succession that finally brought the carnage to an end. First, several brave individuals at the scene – including a tribal employee – tackled Rhoades as she moved the knife toward another victim. They managed to wrestle her to the ground just outside the building, struggling to disarm her despite the danger. Almost simultaneously, Alturas Police Chief Ken Barnes and other officers arrived on site, having been alerted by the City Hall staff and 911 calls. The officers saw Rhoades running outside clutching the bloody knife, but thanks to the intervening bystander they were able to quickly subdue and arrest her in the parking lot without further injury. Chief Barnes noted that Rhoades had expended all her ammunition by that point. The arrest was dramatic – Rhoades, disheveled and blood-spattered, was pinned down and handcuffed on the spot where moments earlier her own family lay dying. Officers recovered two semi-automatic handguns from the scene (indicating Rhoades had brought a backup weapon, though it’s unclear if she fired both). They also took custody of the butcher knife used in the stabbing attack. The tribal office was secured as a crime scene. Within minutes, ambulances and additional law enforcement swarmed the area. Survivors Melissa and Monica Davis were rushed to a hospital in Redding in critical condition – both had suffered gunshot wounds and knife lacerations but, remarkably, would survive after emergency treatment. The newborn baby of Angel Penn was found alive, cradled by a family member amid the chaos.

Modoc County Sheriff’s deputies and Bureau of Indian Affairs personnel also responded to support the small Alturas police force. The violence was over in a matter of nine minutes, but its toll was catastrophic: four people were dead – half of the tribe’s leadership wiped out – and “two more gravely wounded”. The Cedarville Rancheria, numbering only a few dozen people, had lost a significant portion of an entire family line in one afternoon. As the dust settled, shock and grief gripped the community. “It’s not something you hear about happening here in Alturas,” one local resident said; people were trembling with fear, urgently trying to confirm if their loved ones were safe. Mayor John Dederick of Alturas noted that the tribe had “pretty much lost their leadership” in the blink of an eye. A sense of disbelief pervaded – even those who knew Rhoades was volatile “never thought” she would go this far. But the unthinkable had happened: a tribal feud over money and power had exploded into one of the deadliest mass shootings in the region’s history, perpetrated by a 44-year-old mother and grandmother against her own kin.

Arrest and Immediate Aftermath

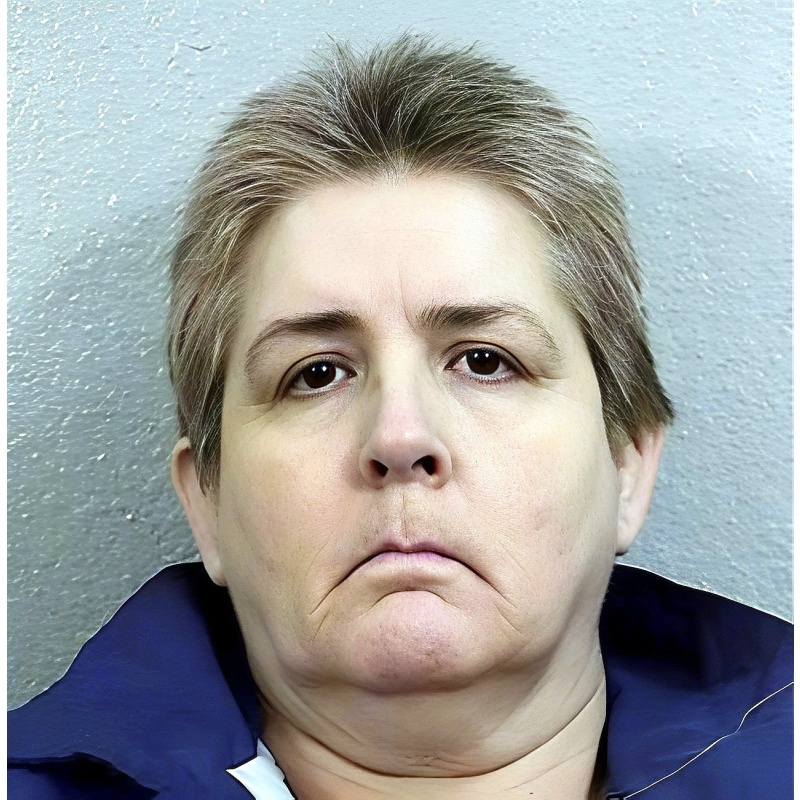

Cherie Lash-Rhoades was taken into custody at approximately 3:35 PM on February 20, 2014, only moments after the massacre. She was arrested by Alturas police at the tribal office parking lot, literally caught in the act of stabbing a victim when officers intervened. Rhoades apparently offered little resistance once subdued; however, Chief Barnes later stated that she did make some sort of statement to police upon arrest before quickly asking for an attorney. The content of her initial statement was not released, but investigators noted her demeanor was unremorseful and angry. Photographs taken that day (an Alturas Police Department mugshot of Rhoades) show her with short spiked hair, a heavy-set build, and a scowling expression – an image that would soon circulate in news reports. Due to the extreme nature of the crime and the fact that many victims were her relatives, authorities took special precautions with Rhoades after the arrest. They held her at an undisclosed secure location rather than the local Modoc County Jail initially, because one of the victims’ husbands was a jail employee and there were concerns about safety or retaliation.

In the immediate aftermath, the small community of Alturas was stunned. Crime scene tape surrounded the tribal office building as forensic teams from the California Department of Justice and the Modoc County Sheriff’s Office processed evidence into the night. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) dispatched a team to provide grief counseling to the tribe, recognizing the profound trauma and loss the surviving members faced. News of the shooting hit national wires by the next day. Media outlets underscored the unusual nature of the incident: a female former tribal leader committing a mass killing at a tribal council meeting. Many noted that female mass shooters are exceedingly rare; Rhoades was one of the very few women in U.S. history to carry out a mass murder, and reportedly the first Native American woman to do so. The story also drew attention because of its bizarre, tragic context – a feuding family at odds over eviction and alleged corruption, leading to bloodshed on sovereign tribal land. The Associated Press and local California newspapers provided grisly details: how Rhoades had shot four people inside and a fifth who tried to flee, then stabbed a sixth when her bullets ran out. They reported how a blood-covered woman ran for help, saving more lives by raising the alarm. Alturas Police Chief Barnes was quoted saying the community was “shocked by the rampage” and that it was “a pretty traumatic event for a lot of people” in such a close-knit town.

Within days, Rhoades was formally charged. Prosecutors filed four counts of first-degree murder and two counts of attempted murder against her in Modoc County Superior Court. Additional special circumstances were attached to the murder charges (multiple homicide and lying-in-wait, among others), making her eligible for the death penalty under California law. She was also initially charged with crimes like child endangerment, since children (including the infant and others in a daycare next door) were placed in jeopardy by her actions. Rhoades was appointed a defense attorney and made her first court appearance on February 25, 2014. For this arraignment hearing, extraordinary security measures were in place. Rhoades was brought into the Alturas courthouse wearing shackles and a bulletproof vest, an unusual step indicating authorities feared possible revenge or violence even in the courtroom. In that initial hearing, she showed no visible remorse. She spoke only briefly to confirm her identity and hear the charges. The judge postponed her plea entry to allow her new attorney time to review the case. When the question of bail arose, it was quickly decided that Rhoades would be held without bail, given the severity of the charges and the risk she posed. She was transferred to a more secure detention facility in another county for the pre-trial period. Modoc County’s District Attorney, Jordan Funk, announced he would seek the death penalty due to the multiple victims and the particularly heinous circumstances of the crime. As the legal process got underway, the small tribe of Cedarville struggled to pick up the pieces. The Cedarville Rancheria Tribal Council, now decimated, canceled meetings for mourning. The tribal housing where Rhoades had lived was vacated, and surviving members of the Davis family and others gathered to support one another. The national Native American community also extended condolences; the President of the National Congress of American Indians, Brian Cladoosby, publicly urged prayers for Cedarville Rancheria and called the incident a grave tragedy for Indian Country.

Court Proceedings: Trial, Verdict, and Sentencing

The criminal case of People v. Cherie Lash-Rhoades moved slowly through the California justice system, taking nearly three years to reach trial. Given the intense local publicity and the fact that almost the entire Modoc County population was aware of or connected to the victims, the venue for the trial was moved out of Modoc County to ensure an impartial jury. The trial ultimately took place in Placer County, California, in late 2016. During the trial, prosecutors methodically laid out the evidence of Rhoades’s guilt. They presented eyewitness testimony from survivors and the woman who ran for help, 911 recordings from that day, and the forensic evidence: two handguns and a knife with Cherie’s fingerprints and the victims’ blood. Jurors heard how Rhoades had planned her attack on the council, bringing weapons to what was supposed to be an administrative hearing. The motive argued by the prosecution was revenge and desperation: Rhoades was about to lose her home and power due to the eviction and the embezzlement probe, and in her anger (and possibly fear of being federally indicted), she decided to eliminate those she blamed – which tragically were her own family members and the tribal employee who had been involved in uncovering her misconduct. The defense, for its part, did not deny that Rhoades was the shooter, but they hinted at her state of mind. They suggested she might have been under extreme mental or emotional disturbance and raised questions about her sanity, though no formal insanity plea was entered. It came to light that Rhoades had no prior criminal record – she had never been arrested before this – but witnesses testified to her history of explosive temper and threatening behavior. The emotional testimony of victims’ relatives, including members of the extended Davis family, underscored the devastation Rhoades had wrought. After a gripping trial, the jury returned a verdict in December 2016: Cherie Lash-Rhoades was found guilty on all four counts of first-degree murder and both counts of attempted murder. The jury also found true the special circumstances (multiple murders), making her eligible for capital punishment.

In the penalty phase that followed, the same Placer County jury had to decide whether Rhoades should be executed or sentenced to life in prison without parole. They deliberated on the enormity of her crimes – a mass murder of family members – versus any mitigating factors. Rhoades’s defense presented some evidence about her difficult life: the poverty on the reservation, her self-described struggles with depression and an undiagnosed mental illness (the defense hinted at possible bipolar disorder or similar issues, though no formal diagnosis was confirmed). They noted she was a mother and grandmother and had been a productive tribal member before things fell apart. However, the prosecution countered with the sheer brutality of the killings and the fact that Rhoades had not shown genuine remorse. Indeed, throughout the trial, Rhoades often appeared cold. At one point, as victim impact statements were read describing the pain she caused, she shook her head and rolled her eyes, exhibiting frustration rather than sorrow. In early January 2017, the jury delivered its recommendation: death. They voted that Rhoades should be sentenced to death for the four murders, reflecting the community’s sense that her act was an unforgivable “slaughtering” of her own family

On April 10, 2017, Judge Candace Beason of Modoc County Superior Court formally sentenced Cherie Lash-Rhoades to death, plus additional decades in prison for the attempted murders and other charges. In a three-hour sentencing hearing, Judge Beason emphasized the atrocity of Rhoades’s actions. She described the killings at the tribal headquarters as “intentional, premeditated and willful” – rejecting any defense notion that it was a momentary snap or that Rhoades was out of control. Rhoades, 47 years old at sentencing, sat in a red jail jumpsuit and reportedly shook her head as the judge read the sentence. Family members of the victims spoke tearfully in court about their immense loss: how children were left without parents, how an entire community’s future was stolen. Rhoades offered no apology. When given a chance to speak, she declined. The judge, following the jury’s recommendation, imposed the death penalty. Additionally, Rhoades received 150 years to life in prison on the attempted murder counts and weapons enhancements – effectively ensuring that even if the death sentence were ever commuted, she would never walk free. The case marked a grim milestone: Rhoades became one of only a handful of women on California’s death row, and the only Native American woman in state history sentenced to death for a mass murder.

Victims and Impact on the Community

The human toll of Cherie Rhoades’s actions was devastating. Four people lost their lives in the shooting, each leaving behind grieving family and a shattered community legacy:

Rurik Davis, 50, Rhoades’s brother, was the tribe’s respected interim Chairman at the time of his death. A father of two, Rurik had stepped up to lead the tribe during the crisis involving Cherie. Described as a calm and fair man, he had been trying to handle his sister’s possible eviction through proper procedure. Rurik died at the meeting he was overseeing, betrayed by the sister he sought to hold accountable. His death left his family – including daughters Melissa and Monica – traumatized and bereaved. Those two young women not only witnessed their father’s murder but were also injured themselves; Melissa and Monica Davis (in their late teens or early twenties) survived bullet wounds and knife cuts and had to undergo multiple surgeries. Physically, they recovered over time, but the psychological scars of seeing their father and other relatives killed have been deep. In victim impact statements, they described nightmares, PTSD, and an unfillable void in their lives.

Angel Penn, 19, Rhoades’s niece, was a bright young mother just beginning her adult life. Angel had a newborn son only weeks old, whom she brought with her to the meeting that day. It’s possible she attended to support her family’s side in the dispute against Cherie. She was cradling her baby when her own aunt shot and killed her. The infant’s miraculous survival was a lone spot of hope in the tragedy – Angel’s baby was unharmed and is now being raised by other relatives, though he will never know his mother. Angel’s death particularly shook her peers; friends remembered her as a gentle, loving young woman. The cruelty of her killing – holding her child – became one of the case’s most cited horrors.

Glenn Calonicco, 30, Rhoades’s nephew, was also killed. Glenn was either a council member or attending relative at the hearing. He was known as a devoted family man (some reports indicate he had a young family of his own). Glenn had grown up in part under Cherie’s roof – one report suggested that Cherie had helped raise him when he was a child. For him to die at her hands added another layer of tragedy. Glenn’s relatives described him as a hardworking and kind individual who got caught in a lethal family feud not of his making. His death meant the loss of a son, a sibling, and possibly a father figure in his own household.

Sheila Lynn Russo, 47, was the tribal administrator and the only victim who was not a blood relative of Rhoades. A mother of two herself, Sheila was an outsider by lineage but had become like family to the Cedarville people through her work. She managed tribal office affairs and was presumably helping coordinate Rhoades’s eviction proceedings. Sheila was shot dead by Rhoades, presumably because she was seen as siding against Cherie in the dispute. Her loss was deeply felt by both the tribe and the broader community. Russo’s children suddenly lost their mother to senseless violence. The incident prompted discussions about workplace safety for those who serve small tribes and sometimes get embroiled in internal conflicts.

Additionally, two people were badly injured but survived:

Melissa Davis, 26 (approximate age), and Monica Davis, 20, Rurik’s daughters and Rhoades’s nieces. Both sisters sustained gunshot wounds; one was also stabbed. Melissa was in critical condition for some time after a bullet wound to her abdomen, while Monica suffered a gunshot through the arm and knife slashes while trying to protect either her father or sister. It is nothing short of miraculous that both lived. They spent weeks in medical care and months in rehabilitation. The psychological impact on them has been profound – not only enduring physical pain but also grappling with the trauma of seeing their aunt commit such an atrocity. Their family noted that the sisters experienced survivor’s guilt and intense anxiety in the aftermath. In later interviews (through family spokespeople at trial), it was said they were “haunted” by the events but were supporting each other in healing.

The psychological impact on the survivors and the tribe has been far-reaching. Members of this tiny Paiute community suddenly found themselves suffering from symptoms of grief and trauma usually seen in war zones. The Bureau of Indian Affairs provided counseling, but many struggled to cope long-term. Trust within the community was frayed; after all, the shooter was one of their own. The fact that all the victims and the perpetrator were related in some way complicated the grieving process – families were torn between mourning loved ones and reckoning with the fact that another loved one had caused it. As one tribal member lamented, “This came as a complete shock to everyone in the tribe… All of these folks are related”. Feelings of betrayal, anger, and confusion were common. Some relatives of Rhoades who survived reported mixed emotions: they loved the Cherie they once knew, but they hated what she had done. The community’s social fabric had been ripped apart in a single afternoon.

The public and media reaction was one of sorrow and astonishment. The case made national headlines in the days after the shooting, highlighting not only the brutality of the act but also raising awareness of intense disputes within some Native American reservations over membership and financial matters. Coverage by outlets such as The Los Angeles Times and The New York Times delved into how a conflict over tribal disenrollment/eviction might have fueled such violence. The narrative of a former leader murdering her family shocked readers. Some media also pointed out the rarity of female mass killers – at the time, Rhoades was often compared to a very short list of women who had committed mass shootings (such as a 2006 postal shooting perpetrator). The Native American press and community blogs discussed the case in the context of tribal politics. An opinion column in Indian Country Today bluntly titled “Justice for victims of Cedarville mass shooting” called for healing and also introspection, asking how warning signs about Rhoades’s behavior were missed. Indeed, it later emerged that authorities had been warned about Rhoades’s temper and threats. Some family members had feared an eruption – Rhoades’s ex-husband Marvin and her grandson had heard her talk about killing people, and one of Rurik’s ex-wives had even mentioned he didn’t trust Cherie around his children. In hindsight, these warnings seem chilling. The Modoc County Sheriff acknowledged that “hindsight is 20/20” but that nothing rose to a level where they could have intervened before the crime. This has been a painful point of reflection for the community and law enforcement alike.

In the aftermath, there were also legal and policy discussions triggered by the case. While no specific new state law arose from it, the tragedy highlighted issues of tribal self-governance and the challenges around evicting or disenrolling tribal members. Some commentators in Indian law circles cited the Cedarville incident as an extreme example of how contentious and destructive disenrollment battles can become. It underscored the need for better conflict resolution mechanisms within tribes and possibly external mediation when family/clan disputes get out of hand. Additionally, many tribes quietly reviewed their security protocols for council meetings. Small tribal offices like Cedarville’s generally had no security guards or metal detectors. After seeing what happened in Alturas, other tribal leaders in California and beyond took note and some implemented stricter safety measures for high-tension meetings (such as having police on standby or moving meetings to secure locations). The Bureau of Indian Affairs also looked into whether there were missed opportunities to catch Rhoades’s alleged embezzlement sooner or to intervene when her suspension and eviction were playing out, though ultimately those internal tribal matters are under tribal jurisdiction.

Incarceration and Current Status

As of 2025, Cherie Lash-Rhoades remains incarcerated on death row in California. Following her 2017 sentencing, she was transferred to the Central California Women’s Facility (CCWF) in Chowchilla, which is where the state’s female death row inmates are housed. There, Rhoades lives in a specialized segregation unit for condemned prisoners. California has not executed any inmate since 2006, and there is currently a moratorium on executions in the state, so Rhoades’s death sentence is in practice a sentence of life imprisonment under high security. She is now in her mid-50s, confined to a cell for most of each day. Prison officials have not released much information about her conduct behind bars, but no major disciplinary issues have been reported publicly. It appears she has not engaged in any notable rehabilitation or education programs in prison – as a death row inmate, her opportunities are limited. Rehabilitation efforts in the conventional sense are minimal; her focus (and that of her legal team) has primarily been on appellate litigation. By law, her case was automatically appealed to the California Supreme Court. Those appeals are ongoing as of 2025, given the complex and lengthy process of capital case appeals. Records show that her attorneys have sought extensions to file briefs, indicating they are combing through trial transcripts for any errors or grounds to overturn the conviction or sentence. However, legal experts widely consider it unlikely that Rhoades will get her sentence reduced, given the strength of the evidence and the egregious nature of the crime.

Within the prison, Rhoades is reportedly an isolated figure. Other female death row inmates in California number only around two dozen, and each case is infamous in its own right (serial killers, child murderers, etc.). Rhoades’s case stands out even among them because she is a rare female mass shooter who killed multiple adults. There is no indication that she has expressed genuine remorse. According to second-hand accounts from a mitigation specialist at her trial, Rhoades tends to justify her actions or remain stonily silent about them. Mental health evaluations in prison have presumably continued, and she may receive some treatment for any diagnosed conditions (for instance, if she has depression or another illness, she might get medication or counseling). But these details are confidential. What is publicly known is that Rhoades’s incarceration has neutralized any direct threat she might pose to society. Behind the thick walls of Chowchilla’s death row, she no longer can harm others. She spends her days in confinement, a far cry from the open expanse of Surprise Valley where she once lived. The state of California, under Governor’s orders, has dismantled the execution chamber at San Quentin and shows no appetite to resume executions, so Rhoades may live out the rest of her natural life in custody.

That said, the future risks or threats associated with Rhoades come chiefly in the form of her potential release, which is extremely implausible. Only a successful appeal or a massive change in her sentence (like a commutation to a term with parole) could ever free her, and there is little to no public support for that outcome. The families of her victims have vowed to oppose any attempt to overturn her sentence. They have attended appellate hearings and spoken about the importance of justice being carried out. In a broader sense, one could say Rhoades remains a cautionary figure – a living reminder of how unchecked fury and entitlement can lead to ruin. Some in law enforcement have noted that if someone capable of Rhoades’s violence were ever at large, they would pose a grave danger; thankfully, Rhoades will never be in that position again. Within prison, there is a minor concern that her temper could lead to altercations with staff or other inmates. However, the death row setting is highly controlled, and any such risk is managed by the fact she’s isolated most of the time.

Lessons Learned and Preventing Future Tragedies

The story of Cherie Lash-Rhoades is a grim lesson in the deadly potential of unresolved conflicts and ignored warning signs. Several key findings emerge from examining this tragedy. First, it highlights how financial wrongdoing and power struggles in small communities can escalate when not addressed transparently. Rhoades was able to wield power as tribal chair for years, and when accusations of embezzlement surfaced, it created a volatile situation. The tribe’s attempt to remove and evict her, though justified, was done in a setting without adequate security or mediation. One takeaway is that outside mediators or law enforcement presence might be prudent in volatile tribal meetings, especially when family and money are involved. The BIA or other agencies could offer support in advance (not just after) when a person with known violent tendencies is being confronted, possibly preventing violence.

Second, the importance of taking threats seriously cannot be overstated. Cherie Rhoades made direct threats to “shoot people” and “blow them away,” as confirmed by her husband and grandson. These were clear red flags. Yet those around her, even loving family, dismissed them as angry talk. After this incident, both tribal communities and authorities are more keenly aware that even in tight-knit families, such threats must be reported and treated with urgency. In retrospect, had mental health professionals or law enforcement been alerted to Rhoades’s threats, perhaps an intervention or restraining order could have been attempted (for example, barring her from the meeting unless she surrendered any firearms). A lesson here is that early intervention in cases of habitual aggression might stop a massacre before it starts. Rhoades had a long history of lesser aggressive acts – e.g., flipping a table in anger – which, while not criminal, signaled a potential for violence. Communities are reminded to develop systems to flag such behavior and get individuals help (anger management therapy, conflict resolution counseling) before they reach a breaking point.

Another lesson relates to tribal governance and disenrollment. The Cedarville case became an example in national discussions about the often contentious practice of disenrolling or evicting tribe members (sometimes due to eligibility disputes or misconduct). As legal scholar Dr. James Diamond noted, frustrations over membership and resources have been “boiling over” in some tribes, and while Rhoades’s massacre is an extreme outlier, it underscores the “deadly trend” that can result from these internal disputes. Recommendations have been made for tribes to create neutral arbitration panels for such disputes or to involve inter-tribal councils to diffuse personal vendettas. Additionally, ensuring accountability and oversight for tribal funds can help prevent the kind of scenario that occurred – if Rhoades indeed stole funds, earlier detection and removal could have happened in a less charged manner, possibly avoiding the dramatic showdown.

From a public safety perspective, a recommendation is that even in small towns, police should be prepared for “it can’t happen here” events. Alturas, with fewer than 3,000 people, likely never imagined a mass shooting in their midst. Now, they and similar communities have learned to train for mass violence incidents regardless of size. The quick response by Alturas Police certainly saved lives that day – their arrival and swift action curtailed Rhoades’s stabbing spree. This reinforces the value of active shooter training and rapid coordination (the fact that City Hall was so near and that staff reacted fast was crucial). Small agencies might consider drills in partnership with local tribes, especially if tensions are known.

For the survivors and the public, another broader lesson is about resilience and healing. The Cedarville Rancheria, though scarred, has worked to heal in the years since. They eventually reconstituted their council (Rurik’s surviving family and other members took on leadership roles) and even continued tribal operations like their health clinic and social services, refusing to let the tribe dissolve. They have honored the victims’ memories through memorials and by sharing their story to help others. The fortitude of survivors like Melissa and Monica – who testified against their aunt in court – shows the power of seeking justice and remembering the lost. One can hope that through counseling and community solidarity, they and others affected have found some measure of peace.

In summary, the case of Cherie Lash-Rhoades teaches that unchecked anger, especially when mixed with family rifts and illicit gains, can be a combustible and lethal combination. It implores authorities and communities to act decisively on early warning signs, to provide avenues for grievances to be resolved without violence, and to ensure there are safeguards (both human and procedural) when life-altering decisions like evictions are on the table. It’s a sobering reminder that even places that seem tranquil – a tribe in the “Empty Quarter” of rural California – are not immune to the worst outcomes of human rage.

Conclusion

Cherie Lash-Rhoades’s descent from tribal leader to mass murderer is a true-crime saga almost too tragic to believe. This narrative has explored her life, the dreadful February 2014 massacre, and the sweeping aftermath – from the grieving families left behind to the courtroom where justice was served. In the end, Rhoades’s name has become synonymous with one of the most shocking betrayals a community has ever endured. The key findings from this case revolve around the dangers of ignoring red flags and the necessity of addressing underlying issues (like embezzlement and disenrollment disputes) before they explode. The lessons learned urge tribal governments and indeed all communities to implement better conflict resolution practices, invest in mental health intervention, and never assume “it couldn’t happen here.” If anything positive is to be drawn, it is that awareness has been raised: families and officials alike are now more vigilant for signs of extreme behaviors, hopefully preventing future Cherie Rhoades from reaching a breaking point.

As of today, Cherie Lash-Rhoades sits in prison, awaiting the outcome of appeals that may take many years to resolve. It is likely she will remain behind bars for the rest of her life, given the gravity of her crimes. The Cedarville Rancheria continues on without her – smaller, but determined to heal. The story stands as a somber chapter in both Native American and criminal justice history, one that will not be forgotten by those who lived it. And in a strange coda to this tale, collectors of crime memorabilia have noted that an autographed item from Cherie Lash-Rhoades would be an exceedingly rare curiosity. Because female mass killers are so uncommon, anything bearing her signature (a letter, a signed photo) might fetch interest for its rarity alone. Of course, such an item’s value is strictly macabre and historical – a footnote in the annals of true crime. The far greater value lies in the lessons her case has taught us about vigilance, justice, and the hope that such a tragedy never repeats.

VIDEO: Death Row Executions- Cherie Louise Rhoades- Native Tribal Leader Kills 4 and Lands on Ca DEATH ROW | https://youtu.be/fpIoTjpEzMc

Archiving Protocol

Payments & Returns

- Payment Methods

- PayPal, Money Order

Postage & Shipping

- Item Location

- 49858, Michigan, United States

- Ships To

- Worldwide

- Pick-ups

- No pick-ups

- Shipping Instructions

- Shipping costs to international destinations will be applied to this auction. Please contact us if you have any questions about shipping to your location.

- Returns Accepted

- No

-800x800.jpg)

-800x800.jpg)

-800x800.jpg)

-500x500.jpg)

-500x500.jpg)